Multi-agent systems are everywhere right now.

Planner agent. Executor agent. Critic agent. Formatter agent. Sometimes even a “manager” agent coordinating everything.

The story is usually the same: if one LLM call can be useful, then several specialised agents working together should be more reliable and produce better results.

But I’m not fully convinced.

Not because multi-agent systems are useless. They can be powerful. I’m just not sure we are always clear about why we use them, and what trade-offs we introduce when we chain probabilistic systems together.

Thinking of an Agent as a Function

Let’s simplify the discussion and treat an agent like a function.

Something like:

f_0_llm_0_step_n(prompt[1..n], data, output_step_n-1)

In plain English:

An agent, running a specific model (say llm_0), performs step n using one or more prompts, some dynamic data (code snippets, documents, context), and the output of the previous run. It then produces a result.

That result is passed to the next agent:

f_1_llm_1_step_n(…)

And so on.

So we create a composition:

f3(f2(f1(x)))

Each f is powered by an LLM. And each LLM call is probabilistic.

Every LLM Call Can Be Wrong

No matter how good the model is:

- It can misunderstand the requirement.

- It can hallucinate details.

- It can omit constraints.

- It can be confidently wrong.

If we assume each step has some probability of being correct (call it a_i), then in a simple independent chain, overall correctness looks roughly like:

a_total ≈ a1 × a2 × a3 × …

Even if each individual step is “pretty good”, multiplying several steps together is not comforting.

But I should be honest about what this model hides. The formula assumes errors are independent across steps. In practice, they’re often not. Agents share the same context, sometimes the same model weights, and frequently the same blind spots. If agent 1 misunderstands an ambiguous requirement, agent 2, reading agent 1’s output, will likely inherit that misunderstanding. Correlated failures can make things worse than the multiplicative model suggests, because the “correction” you’d hope for from chaining doesn’t materialise when all the agents are confused in the same direction.

On the other hand, if agents are operating on genuinely different aspects of a problem, the correlation drops and you get closer to the independent case, which is actually more optimistic.

The point is not that the formula is a precise model. The point is directional: chaining probabilistic transformations does not automatically improve reliability, and in many setups it degrades it. The exact shape of that degradation depends on how correlated the failure modes are.

“Yes, But Agents Can Correct Each Other”

A fair counterargument is: this is too pessimistic.

People will say:

- We use critic agents.

- We use voting.

- We do retries.

- We enforce JSON schemas.

- We run compilers and tests.

- We keep temperature low.

And yes, these things change the math.

If you add deterministic constraints between steps, you are no longer doing a blind probabilistic chain. You are building something closer to:

LLM → deterministic constraint → LLM → deterministic constraint

That is why agent workflows often work much better for code generation than for pure reasoning. A compiler or a test suite is a hard boundary. It can reject invalid outputs and force correction.

So the argument is not “multi-agent is always bad”.

The real risk appears when we build deep chains without strong external anchors.

Two Problems That Look Like One

The issue I worry about most in deep chains is what I’d call epistemic drift. But when I try to pin it down, it splits into two distinct problems that need different solutions.

The first is error accumulation. Each agent tends to assume the previous output is “good enough”. It builds on it, improves it, adds structure. If agent 2 introduces a small wrong assumption, agent 3 doesn’t question it. It elaborates on it. By agent 5, the wrong assumption is load-bearing and invisible. This is a propagation problem, and the fix is intermediate validation: check facts, run tests, enforce constraints between steps.

The second is confidence inflation. As the chain gets deeper, outputs become more organised. They sound more authoritative. They look more complete. But coherence is not the same as correctness. A well-formatted, well-structured document can be built on a shaky premise and still read as though every claim was carefully verified. This is a calibration problem, and it’s worth noting that it isn’t unique to multi-agent systems — a single LLM call can also produce overconfident nonsense. But multi-agent chains make it worse, because each successive agent treats the previous output as settled ground rather than as probabilistic input.

The distinction matters because people often propose critic agents or voting as the solution. Those help with error accumulation. They do very little for confidence inflation. A critic agent reading a polished, internally consistent document has the same struggle a human reviewer does: the text doesn’t signal where its weak points are.

And in both cases, the deeper the chain, the harder it becomes to locate where things first went wrong.

Debugging Becomes Hard

With one LLM call, debugging is simple: inspect the prompt and output.

With five agents:

- Which agent introduced the wrong assumption?

- Which agent “fixed” something that wasn’t broken?

- Which step created the hallucinated constraint?

- Which retry changed the meaning?

Multi-agent workflows increase the number of places where subtle divergence can happen. I think of it as increased epistemic surface area: more surfaces where mistakes can stick.

This matters in areas like architecture decisions, long-horizon planning, policy and compliance, regulated environments in finance or healthcare or infrastructure. In these contexts, a small drift can turn into an expensive mistake.

Humans Are Also Probabilistic

To be fair, humans are not deterministic either.

Humans misunderstand specs. Humans propagate assumptions. Humans get tired, biased, distracted. You could model a human step as:

h(context, bias, fatigue, memory)

So the comparison is not “agents vs perfection”. It’s agent chains versus human chains. And sometimes multi-agent systems may be no worse than multi-human workflows.

The strongest version of the counterargument goes further: multi-agent systems with critic loops are basically peer review, and peer review empirically reduces error rates. That’s true. But there’s a reason the analogy breaks down. Human peer reviewers bring genuinely independent perspectives. They have different training, different experiences, different biases. When a second engineer reviews your design, they might catch the thing you missed precisely because they think differently.

LLM agents, even when given different system prompts, share the same training data, the same learned biases, the same blind spots. A “critic” agent running the same model as the “creator” agent is not an independent reviewer. It’s closer to asking the same person to review their own work after taking a coffee break. It might catch surface errors, but it’s unlikely to challenge the deeper assumptions because it shares them.

This doesn’t mean multi-agent critique is worthless. It means the error reduction you get from it is probably smaller and less reliable than the error reduction you get from genuine human peer review, and we should set our expectations accordingly.

Why Multi-Agent Often Means Multi-Model

There is another reason multi-agent systems are popular, and it’s not always about “better reasoning”.

It’s cost.

In practice, a lot of multi-agent pipelines are also multi-model pipelines:

- a cheap model for classification or routing

- a mid-tier model for extraction

- a strong (expensive) model for reasoning

- a cheap model again for formatting

So when people say “agentic workflow”, sometimes they actually mean: we split the work so we can run most steps on cheaper models.

That’s not a bad idea. It’s rational.

If you run everything on the strongest model, costs explode. So people route tasks.

But this introduces a specific risk: the smaller, cheaper models often become gatekeepers. If a cheap model misclassifies a task as “simple”, the expensive reasoning step might never run. Now the system is not optimising for correctness. It is optimising for cost, and correctness becomes a side effect.

I want to be precise here, because this is not inherently a flaw of multi-agent design. A well-built system can route uncertain inputs upward, using confidence thresholds, fallback paths, or escalation logic. The problem is that many systems don’t. The default in most frameworks is to route based on classification alone, without a notion of “I’m not sure, send this to the bigger model.” And when cost pressure is the main driver, the incentive is to keep things on the cheap path.

The other issue with mixing models is that you’re now mixing failure modes. Different models have different biases, different calibration, different hallucination patterns. You are no longer chaining one probabilistic system. You are chaining several different ones. That doesn’t make the system inherently worse, but it does make behaviour less predictable and debugging harder. When something goes wrong in a multi-model pipeline, you’re not just asking “what went wrong?”, you’re asking “which model’s particular flavour of wrong caused this?”

The Human Validation Problem

There is also an economic problem around validation.

The obvious extremes are: validate every intermediate step (which destroys the automation benefit) or validate only the final output (which means rerunning the whole pipeline when it’s wrong, and re-validating from scratch because stochastic outputs change between runs).

Most production systems land somewhere in the middle. You identify high-risk steps and validate those. You let low-risk transformations run autonomously. You put hard checkpoints at the boundaries where errors would be most expensive.

That middle ground is reasonable, and it works. But it’s worth noticing what it implies: the value of the multi-agent system now depends entirely on how well you’ve identified where the risk concentrates. Get that wrong and you’re either over-validating (killing the efficiency gains) or under-validating (letting errors through at the exact points that matter).

In other words, agent workflows don’t remove validation cost. They require you to be much more deliberate about where you spend it.

When Do Multi-Agent Workflows Make Sense?

In my view, multi-agent workflows make sense when they are constrained and anchored.

For example:

- each step has a clearly bounded responsibility

- deterministic validation exists between steps (tests, schema checks, compiler, policy engine)

- intermediate outputs have stable structure

- chain depth is limited

- retries are controlled and predictable

- there is traceability (you can see what changed and why)

- routing logic includes uncertainty-aware escalation, not just classification

In that world, multi-agent can genuinely improve quality and reduce human workload.

But without those constraints, adding agents can increase complexity faster than it increases correctness.

The Real Question

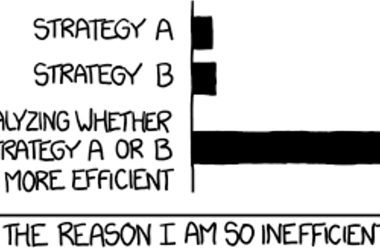

The real question is not “Are multi-agent systems good or bad?”

It’s:

Are we increasing reasoning depth, or just adding reasoning layers?

Sometimes multi-agent systems create better output. Sometimes they create more confident output.

Those are not the same thing.

Final Thought

We’ve seen this pattern before in software engineering.

More lines of code did not mean more value. More microservices did not automatically mean better architecture. More tokens do not necessarily mean more productivity.

That last one is worth sitting with for a moment, because the industry consensus on microservices is instructive. We didn’t conclude that microservices were wrong. We concluded that they require operational maturity to work — good observability, clear service boundaries, robust deployment pipelines. Without that maturity, they made things worse. With it, they could be genuinely better than the monolith.

I think multi-agent systems are at a similar inflection point. The pattern is not wrong. But it demands more rigour than most teams are currently applying. It demands deterministic anchors, good traceability, honest assessment of where errors concentrate, and a willingness to keep things simple when the constraints aren’t there yet.

More agents do not necessarily mean more correctness. But well-constrained agents, with strong validation boundaries and honest routing, can earn their complexity.

The danger is in the middle: systems that look sophisticated, that sound confident, that cost less per token, while quietly amplifying the exact problems we wanted to solve.

Note: As I’m not a native English speaker, I used ChatGPT to review and refine the language of this article while keeping my original tone and ideas.

Originally published on Medium.